Delft's city government

and the roles played by Antony van Leeuwenhoek and his family, friends, and colleagues

Leeuwenhoek was actively involved in Delft's city government for most of his life. To understand the minor role he played, it is helpful to understand the context, the structure of Delft's city government.

The menu on the left sidebar provides details about the documented involvement of Leeuwenhoek and his family, neighbors, and colleagues in Delft's city government. The menu on the right side bar provides details about the structure and functions of the city's government as it had developed by Leeuwenhoek's time.

The menu on the left sidebar provides details about the documented involvement of Leeuwenhoek and his family, neighbors, and colleagues in Delft's city government. The menu on the right side bar provides details about the structure and functions of the city's government as it had developed by Leeuwenhoek's time.

This government developed gradually after 1246 as the City reached it full size and gained autonomy and self-governance. The government matured when Delft took a role as one of the important cities in the Dutch Republic, along with Amsterdam, Leiden, Haarlem, Utrecht, and Dordrecht.

By 1654, when Leeuwenhoek returned from his apprenticeship in Amsterdam, the City's structure, laws, and processes were solidly in place and would remain essentially the same for another seventy years after his death. The most visible symbol of political power was the City Hall, called the Raedthuis, or council house, in the image on the left. Leewenhoek worked there for almost forty years.

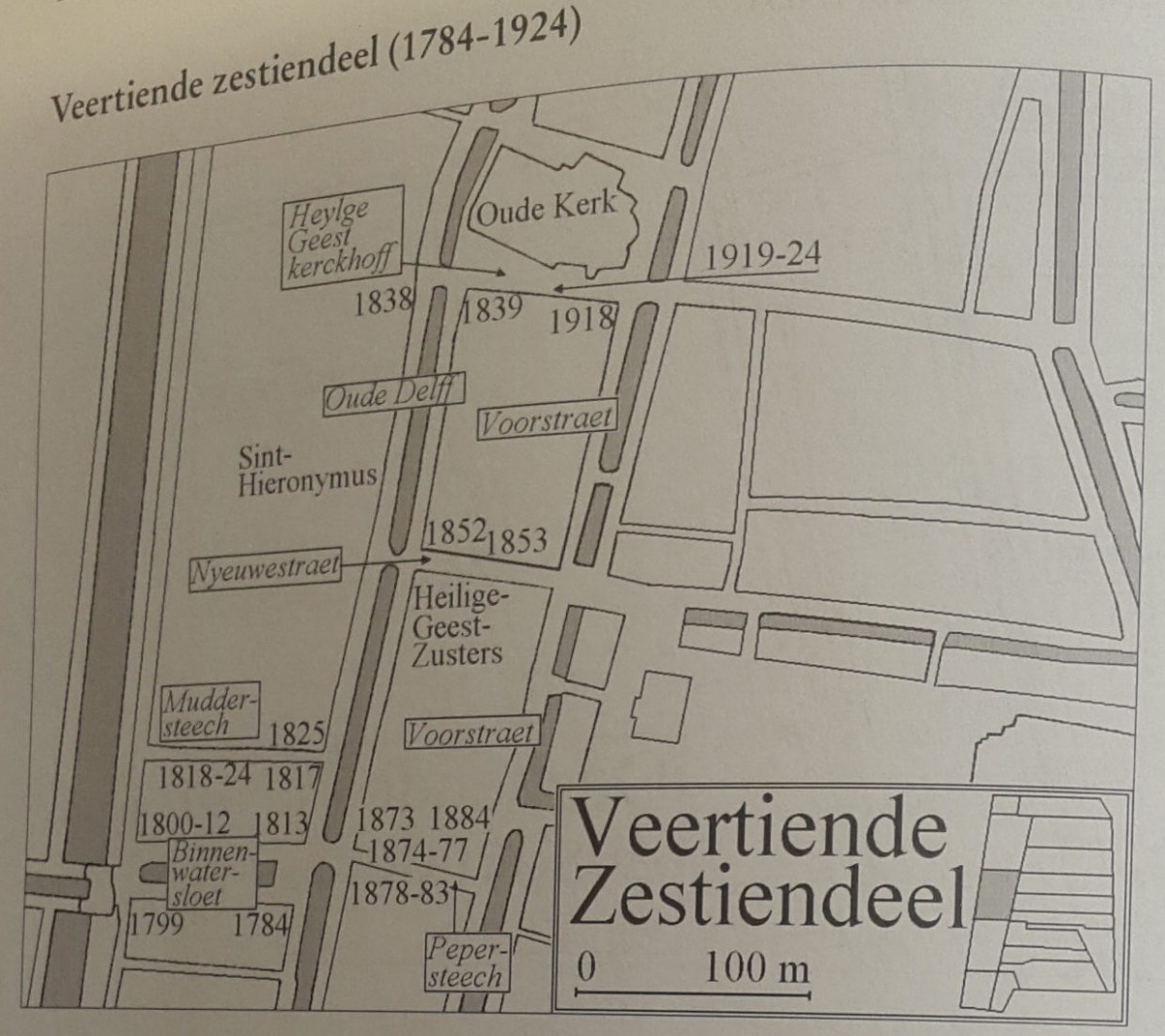

For administrative purposes such as the Familiegeld (estate tax) in 1674, the city was divided into 16 districts. These districts were established for the tiende penning (tenth penny, tithe) tax in 1543. The map below right from Gerrit Verhoeven's Het eerste kohier shows Leeuwenhoek's district, the 14th. His house was in the center, just to the right of the 3 in 1853. The inset map of the whole city shows the sixteen districts, numbered clockwise from the top right. An extension of the 16th in the northwest corner of the city included the Buitenwatersloot. Another two districts lay outside the walls to the southeast.

For administrative purposes such as the Familiegeld (estate tax) in 1674, the city was divided into 16 districts. These districts were established for the tiende penning (tenth penny, tithe) tax in 1543. The map below right from Gerrit Verhoeven's Het eerste kohier shows Leeuwenhoek's district, the 14th. His house was in the center, just to the right of the 3 in 1853. The inset map of the whole city shows the sixteen districts, numbered clockwise from the top right. An extension of the 16th in the northwest corner of the city included the Buitenwatersloot. Another two districts lay outside the walls to the southeast.

For self-defense purposes, the city was divided into four sections for the civic guards. Finally, in spite of the Reformation, the old Roman Catholic parish system was still a useful reference.

Historians of the period divide the City's officials, paid and unpaid, into various groups, sometimes two or three, sometime more. The lists on the right sidebar adapt the five groups laid out in Gerard Van Roon's indispensible Macht en Gewoonte in Het Delftse Stadsbestuur (p. 45). Roon notes that a survey or overview of the people in service to the city is a "complex exercise" (complexe exercitie) and has been done only by Raadschelders in Plaatselijk Bestuurlijke Ontwikkelingen.

1 The political managers (regenten)

They were regents who served on the Council of Forty. They managed the VOC office and served as delegates to provincial and national councils. They -- and some of their wives and daughters -- served on the boards of social welfare institutions. They rarely received payments for their services.

This group also includes the city's treasurers and members of the Heeren van de Wet (law officers): the sheriffs, mayors, and magistrates.

2 The higher city officials (hoge ambtenaren)

Also from regent families, usually with fixed salaries: pensionary, the two city secretaries, and supervisors of social welfare institutions providing for the poor, sick, and aged. The pensionary, the two city secretaries were also members of the Heeren van de Wet. In addiiton, I am including in this group the officers of the civic guard and the harbormasters.

3 The lower city officials (kleine officieren)

Seldom from regent families, they were usually paid; the trash supervisors (crebbemeesters), for example, were not. Most of Leeuwenhoek's city jobs fell into this category but dozens of citizens were filling these positions: messengers, clergymen, teachers, even those who kept watch at night from the city's towers.

4 The registered city officials (geadmitteerde functionarissen)

They had to be appointed or designated by the City, usually the mayors, but they were not paid by the city. Prominent examples are notaries and lawyers. This category also includes Leeuwenhoek in his role as city wine gauger (wijnroeier). He was appointed by the City and was supposed to stay neutral and objective in his measurements, as well as stay out of the wine trade. However, he was paid by the tax farmers (pachters) and the payments are recorded in notary documents, not in the city treasurer's account books.

5 The suppliers (leveranciers) of goods and services

For example, the city periodically bought peat, fire-fighting buckets, and paper and writing materials. It also paid for maintenance and repair of city property: painting, glassworking, and carpentry. Several of Leeuwenhoek's relatives as well as some of the other lower city official also supplied some of these goods and services. For example, fellow camerbewaarder Daniel Bogart regularly delivered a load of peat toward the end of the winter.